Take Delight in the Ancient Art of Kite Flying in Taipei

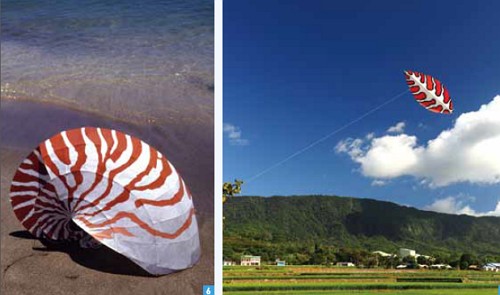

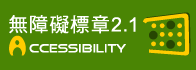

Two-and-a-Half Millennia of Kite History The first known human flight using a kite took place in 550 CE. At the time the court of the Eastern Wei (東魏) was occupied, and Huangtou (元黃頭) was placed in captivity and later flown against his will from the tower of Yecheng (鄴城). Around this time, kites made of paper also made their first appearance, though today the finest Chinese kites are still made of hand painted silk with a split golden bamboo frame. Cheap, mass-produced kites are generally made of printed polyester. From China, traders later exported kite technology to Korea, Japan, and across Asia to India. To this day, kite flying remains exceptionally popular in the Indian subcontinent, Central Asia and the Middle East, where kids engage in kite fighting, an activity featured in the Afghan novel and film adaptation of The Kite Runner . Stories of kites did not reach Europe until Marco Polo brought illustrations of dragon kites on military banners back from China in the 13th century. The Europeans regarded kites as mere curiosities and the stories had little impact on their culture. It was not until much later that great Western thinkers such as Benjamin Franklin and Alexander Graham Bell began to use kites in their experiments on the weather. The use of kites was instrumental in the research of Orville and Wilbur Wright. The world's first plane, flown by the brothers in 1903, was in fact a type of kite. In World War I, various European powers relied on the kite for enemy observation and signaling. After the use of airplanes became firmly established, kites were rendered obsolete and became more common for recreational purposes. Today, flying kites still brings ecstatic joy to children around the globe. At the age of 10, Buteo Huang (黃景楨), flew his first kite with his brother. Watching it float in and out of the clouds on that fateful day sparked a lifelong obsession. He made his own kite using paper from old calendars and sticky rice glue. For most children, the main purpose of making a kite is to fly it. “But I was different from other kids,” explains Huang. “I was more interested in the design process than actually flying it.” Throughout high school, Huang created larger and increasingly intricate kites. Pushing the boundaries of kite making, he experimented with a wide assortment of materials including newspaper, aluminum foil, cotton, polyester, and colored cellophane. In college, Huang cons t ructed Pegasus , an enormous, flying white horse. “Only once it was taken to the mountains and unleashed in the sky, fluttering in its natural setting, was the piece truly complete.” In this manner, Huang (now calling himself Buteo, the Latin word for “hawk”) transformed the kite from an object for children's entertainment into a form of installationper formance art. That kites are merely a toy is a widespread belief that Huang would dedicate the rest of his life to destroying. Cutting-Edge Ideas Executed With a Majoring in architecture, Buteo went on to found an interior design business. After one of his kites won two awards at the 2002 Holland International Kite Festival, he decided to shut down his company and make kites full time. However, his education in architecture and design strongly impacted his approach to kite making. “Everything in the world has a function. The primary function of a kite is to fly. Every single one of my kites can fly.” Buteo also insists that every kite must be user-friendly. He often tests them out publicly, asking random passersby to try. Even his bulkiest kites can be disassembled in a matter of minutes and transported with ease. Buteo was determined to push kite making to an even higher level. Many consider his next move to be his most revolutionary: creating a kite series that was not only elegant but also conveyed a message of conservation. The collection was decorated with tree rings, making it a public statement about deforestation and the effects of human activities on the environment. Kites became a vehicle for transmitting Buteo's thoughts and concerns. Another piece, Chinese Crested Tern is a life-sized replica of a species of bird thought to be extinct until four pairs were rediscovered on Taiwan's Matsu Islands (馬祖列島) in 2000. According to Buteo, kite making requires the perfection of certain skills and techniques, but ideas are still what are most important. “Kites are an extension of my mind. By flying a kite, I can send my ideas into the sky for everybody to observe.” Many have described Nautilus as Buteo's greatest work. A large-scale replica of a red and white mollusk, it took him five years and three prototypes to get it airborne. However, Buteo does not regard it as his masterpiece. Instead, he chooses Dreams Come True, a series of shooting stars made of garbage bags. “As children we are told to make a wish when we see a shooting star, but we never have time to make the wish before the star disappears. This piece allows people ample time to make their wishes.” The kites make use of an innovative new technique in kite design developed by Buteo, one that has a simpler structure and requires no running or tugging to keep afloat. Over a Decade Under the International Spotlight In 2006, Buteo was invited to exhibit 307 of his kites at the Winter Garden in New York City's World Financial Center. The centerpiece of the exhibit was the Tao Canoe. This multi-oared vessel is a prominent symbol of the Tao tribe, a threatened culture that lives on Taiwan's Orchid Island (蘭嶼). Suspended in the building's atrium, the massive canoe was surrounded by flying fish, the focal point of the Tao's most important festival. During this annual tribal celebration, masterfully constructed canoes are hoisted into the air by men in white loincloths and taken to the sea to welcome the season of flying fish, which provide a major food source for the island's inhabitants. If you want to try your hand at kite flying, Taipei City is the perfect venue because it offers strong winds yearround. Taipei's extensive network of riverside parks offer the ideal setting. The National Dr. Sun Yat-sen Memorial Hall is a favorite place to buy and fly kites, though they can also be purchased from stationery stores across the city. According to Buteo, rooftops in Taiwan also make great places to fly kites! You may already be aware that the Chinese are credited with the invention of gunpowder, noodles, and printed books. However, did you know that the kite also came into being in China? Kites have been tied to Chinese culture since the Zhou dynasty (周朝). Today, the city of Weifang (濰坊市) in Shandong Province (山東省) is considered the kite capital of the world, and is home to the 8,100-square-meter Weifang World Kite Museum (濰坊世界風箏博物館). The city has also hosted the annual International Kite Festival since 1984. This love of kite flying transferred to Taiwan long ago, and remains enormously popular. Most Taiwanese adults have fond childhood memories of learning how to make kites in school. Let's explore the roots of this liberating, ancient activity.

You may already be aware that the Chinese are credited with the invention of gunpowder, noodles, and printed books. However, did you know that the kite also came into being in China? Kites have been tied to Chinese culture since the Zhou dynasty (周朝). Today, the city of Weifang (濰坊市) in Shandong Province (山東省) is considered the kite capital of the world, and is home to the 8,100-square-meter Weifang World Kite Museum (濰坊世界風箏博物館). The city has also hosted the annual International Kite Festival since 1984. This love of kite flying transferred to Taiwan long ago, and remains enormously popular. Most Taiwanese adults have fond childhood memories of learning how to make kites in school. Let's explore the roots of this liberating, ancient activity. Legend has it that the kite was invented when a Chinese farmer tied a string to his hat to prevent it from blowing away. According to more reliable historical records, in the 5th century BCE the philosopher and inventor Lu Ban (魯班) built a wooden bird capable of remaining in flight for three days; this is considered the prototype of the first kite. The fine silk for which ancient China was famous provided the perfect material for kites, and for the high-strength, tensile string needed to fly them. Bamboo, a highly resilient substance, also provided a strong yet lightweight frame. In early times, kites were primarily functional devices flown to send messages, communicate information on military operations, and conduct meteorological testing. In 200 BCE, during the Han dynasty (漢朝), General Han Xin (韓信) flew a kite over the wall of the city his soldiers were attacking in order to determine how long the tunnel he was about to dig under the walls would have to be. His calculations were correct, his tunnel a success, and his army was victorious.

Legend has it that the kite was invented when a Chinese farmer tied a string to his hat to prevent it from blowing away. According to more reliable historical records, in the 5th century BCE the philosopher and inventor Lu Ban (魯班) built a wooden bird capable of remaining in flight for three days; this is considered the prototype of the first kite. The fine silk for which ancient China was famous provided the perfect material for kites, and for the high-strength, tensile string needed to fly them. Bamboo, a highly resilient substance, also provided a strong yet lightweight frame. In early times, kites were primarily functional devices flown to send messages, communicate information on military operations, and conduct meteorological testing. In 200 BCE, during the Han dynasty (漢朝), General Han Xin (韓信) flew a kite over the wall of the city his soldiers were attacking in order to determine how long the tunnel he was about to dig under the walls would have to be. His calculations were correct, his tunnel a success, and his army was victorious. Taiwan's Very Own Kite-Making Legend

Taiwan's Very Own Kite-Making Legend  n Architect's Precision

n Architect's Precision  When asked whether he feels he has been successful in changing people's perceptions of the kite, Buteo used to reply with a firm “no.” Now he says “partially.” Besides the Winter Garden, he has also exhibited at the Principe Felipe Science Museum in Spain and the National Taiwan Museum (國立臺灣博物館) here at home. He has constant requests for custom designs and his kites have sold for as much as NT$350,000. It appears that at least some people are starting to accept kites as a viable medium of art. But Buteo feels he still has a lot of work to do with the general public. Buteo has finally achieved the recognition that he deserves as one of the world's greatest kite designers. His creations showcase the natural fauna and traditional culture of Taiwan, making him a national treasure. He has published a book introducing kites, and his current goal is to open a museum showcasing his work. Buteo also trains local schoolteachers in kite making and is working on his second book. Keep an eye out: starting next year, he will begin selling kites at key locations across Taiwan.

When asked whether he feels he has been successful in changing people's perceptions of the kite, Buteo used to reply with a firm “no.” Now he says “partially.” Besides the Winter Garden, he has also exhibited at the Principe Felipe Science Museum in Spain and the National Taiwan Museum (國立臺灣博物館) here at home. He has constant requests for custom designs and his kites have sold for as much as NT$350,000. It appears that at least some people are starting to accept kites as a viable medium of art. But Buteo feels he still has a lot of work to do with the general public. Buteo has finally achieved the recognition that he deserves as one of the world's greatest kite designers. His creations showcase the natural fauna and traditional culture of Taiwan, making him a national treasure. He has published a book introducing kites, and his current goal is to open a museum showcasing his work. Buteo also trains local schoolteachers in kite making and is working on his second book. Keep an eye out: starting next year, he will begin selling kites at key locations across Taiwan.  Kite Flying in Taiwan's Windy Capital

Kite Flying in Taiwan's Windy Capital

![Taiwan.gov.tw [ open a new window]](/images/egov.png)