The Diabolo Spins Its Way from Ancient China to the Modern Stage

The diabolo, or Chinese yo-yo, consists of an axle with a disk on either side, spinning on a string tied to two sticks that are held in the player’s hands. The term diabolo is a modern name derived from the Greek dia bolo, meaning “across throw.” However, the Chinese yo-yo, like the regular yo-yo, has origins in China that go back thousands of years. Many believe that the Chinese yoyo is as much a symbol of Taiwanese culture as the sky lantern or dragon boat. As such, looking at the history of the Chinese yo-yo is akin to examining the history of Taiwan itself. The original Chinese yo-yo was known as kong zhu (空竹) or “hollow bamboo.” Unlike the modern diabolo, the wheels on either end were flat. The oldest one was found in Shanxi Province (山西省) in China, and dated back more than four millennia. The Chinese yo-yo’s shape was standardized in the Ming dynasty (明朝), but due to its long history, it has a number of different names, including kong zhong (空鐘) or “hollow bell,” since the grooves in the sides of its wheels make whistling noises when it is spun. Most Taiwanese refer to it as che ling (扯鈴). Throughout the majority of China’s history, the Chinese yo-yo was used in acrobatic performances. Highly skilled players tossed it to great heights, catching it behind their backs, passing it to other performers, and so on. These performances abided by rigid rules con- cer ning cos tumes , makeup, and movements that were in line with those of traditional opera and acrobatics. This form changed very little over the centuries. In the early 19th century, French and British travelers brought the Chinese yo-yo to Europe. The Europeans, who called it “devil on two sticks,” made several adaptations to the ancient toy. Some employed metal cups on either end, while others were made of wood. In Victorian times, British aristocrats developed a tennis-like game using the Chinese yo-yo, in which they wore dainty white outfits and adopted elegant poses as they tossed the yo-yo back and forth. In 1905, a Frenchman named Gustave Phillippart designed and patented the modern diabolo. His version had large cones on either side and was made of rubber, making it more durable than wooden and bamboo varieties, which broke easily. His design was reintroduced to China and Taiwan in the late 20th century, where it is now the standard. The diabolo fell out of fashion in Europe, but they have become extremely popular toys in China and Taiwan. The first Chinese yo-yos to enter Taiwan were of the original bamboo variety. They were brought over by groups such as the Li Tang-hua Acrobatics Troupe (李棠 華雜耍技藝團) which fled to Taiwan with the KMT (Kuomintang, or Chinese Nationalist Party; 國民黨) in the late 1940s. Since then, diabolos have become an integral component of physical education classes for all public school students in Taiwan. The journey that would take Liu Lechun (劉樂群) from elementary school teacher to the director of Taiwan’s most mesmerizing diabolo performance troupe began out of the blue. In 1986, Liu had just graduated from college and was doing an internship at Taipei Municipal Zhong Zheng Elementary School (台北市中正國民小學). One day, the principle gave him a box of diabolos and told him he was the diabolo club leader. “I didn’t choose the diabolo, the diabolo chose me,” he now says. Liu’s lack of formal training freed him from the strict conventions of traditional diabolo playing. “Actually, I had always been a weirdo. In college, I joined the ballet club, studied music, and made strange drawings.” Accustomed to thinking outside of the box, Liu had incredibly high hopes for his student group, which he named Youth Diabolo Dance of Taipei. He envisioned transforming it from a bunch of kids playing with diabolos into a professional diabolo dance group. Liu’s dream gradually materialized. As the original group members grew older they became more experienced and their skills more refined. Liu invited teachers of dance and theatrics to complement his diabolo lessons. The group’s reputation grew, and in 1994 they performed at the Double Ten Day (雙十節) celebration at the National Chiang Kai-shek Memorial Hall. According to Liu, his group’s true turning point came in 2002, when they were invited to perform at the Lincoln Center Arts Festival in New York City. Faced with the challenge of performing on a truly professional stage, it was the first time the group collaborated with a full range of theatre artists, including composers, costume designers, and makeup artists. Liu also hired the group’s first paid performers to lead the shows and guide the younger novices. In 2005, he quit teaching to focus all his energy on leading his diabolo dance troupe. The Diabolo Dance Theatre is Born To commemorate the troupe’s transition, Liu Lechun christened the group the Diabolo Dance Theatre (舞鈴 劇場). For their first major production, entitled The Game (嬉遊舞鈴), they were one of five groups to represent Taiwan at Expo 2005 in Aichi, Japan. Lin Hwaimin (林懷民), whose legendary Cloud Gate Dance Theatre (雲門舞 集) performed the day after the Diabolo Dance Theatre, was so impressed with Liu’s production that he later contacted him to arrange a collaboration. In order for Liu’s diabolo players to perform to Cloud Gate’s preferred classical music, the diabolo itself had to be modified. Liu invented a ball bearing system with reduced friction that allowed it to spin twice as fast and for longer periods of time to the slower music. Liu also invented diabolo wheels with a soft rubber exterior to prevent his younger students from getting injured when flying diabolos went astray. So inspired was Liu by Cloud Gate’s professionalism that it sparked in him a renewed commitment to revolutionizing the art of diabolo playing. “After working on a production for up to two years, then finally seeing it performed, it is like a child being born. However, I’m constantly thinking of ways to improve it, new elements that can be added.” These elements have included everything from laser beams and black lights to clowns on unicycles and roller skates. For Ocean Celebrations (海洋慶典), dancers in huge plastic balls, trapeze artists, live drummers, and singers were added to the mix, the latter singing in an invented language with phonetic elements from Taiwan’s aboriginal languages. The production has truly captivated audiences with its dazzling effects and daring stunts. In 2012, the Diabolo Dance Theatre performed Ocean Heart in Nicaragua, El Salvador, Guatemala, and Paraguay. In September and October of this year, they will once again take Ocean Celebrations to Latin America, as well as to Las Vegas. Despite all the acrobatics, the diabolo remains the focal point of the show. For his next production, Infinity, Liu is taking diabolo performance back to its Chinese roots. For this, his most ambitious project to date, Liu is attaching digital sensors to the diabolos to record their paths and project them onto a screen. The incandescent trail created represents the continuous flow of qi (氣) through the four seasons. Until now, the Diabolo Dance Theatre has adhered to largely Western inspiration in its costumes and theatrics, with comical injections and circus-inspired flair. Viewers can expect Infinity to exude a more classical, meditative yin yang (陰陽) vibe, simultaneously avantgarde in its technology and classically Chinese in its thematic delivery. After my discussion with Liu Lechu, I asked him to show me some basic diabolo steps. He shied away from my invitation, instead beckoning to his star performer, Ivy Yang (楊心怡) to show me the ropes. While mastering advanced diabolo moves requires years of practice (Yang, the group’s longest member, has been with the troupe for 21 years), the basic techniques can be picked up by anyone in a matter of minutes. On my first attempt tossing the diabolo, I pulled too hard. Shrieking in fear, I covered my head and dove aside as the diabolo flew into the air and then hit the floor with a thud. However, after a little guidance from Yang and a few more tries, I was able to successfully launch the diabolo and catch it. There is a real sense of satisfaction when you feel this ancient toy spinning rapidly under your control. The diabolo is a true gateway to 4,000 years of Chinese culture, so why don’t you give it a try? The Chinese Yoyo: 4,000 Years of History

The Chinese Yoyo: 4,000 Years of History From Math Teacher to Professional Theater Director

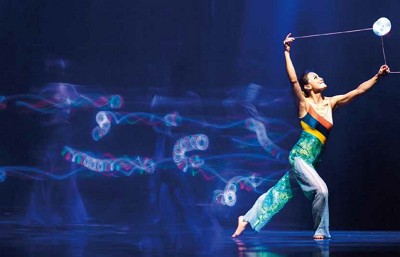

From Math Teacher to Professional Theater Director For the 2007 production Ocean Heart (海洋之心), Liu’s latest inventions, a diabolo inlaid with LED lights and a single sided monobolo were used. Many Taiwanese first encountered the Diabolo Dance Theatre at the 2010 Taipei International Flora Exposition, where they gave 212 consecutive performances. At the end of the expo, Liu rented the Butterfly Hall (舞蝶館) for another three months to perform Entrance (奇幻旅程), a carnival-like production that featured performers costumed as creatures emerging from an entranceway and prowling amongst the audience.

For the 2007 production Ocean Heart (海洋之心), Liu’s latest inventions, a diabolo inlaid with LED lights and a single sided monobolo were used. Many Taiwanese first encountered the Diabolo Dance Theatre at the 2010 Taipei International Flora Exposition, where they gave 212 consecutive performances. At the end of the expo, Liu rented the Butterfly Hall (舞蝶館) for another three months to perform Entrance (奇幻旅程), a carnival-like production that featured performers costumed as creatures emerging from an entranceway and prowling amongst the audience. Try the Diabolo for Yourself!

Try the Diabolo for Yourself!

![Taiwan.gov.tw [ open a new window]](/images/egov.png)