Taiwanese Opera--the People's Opera

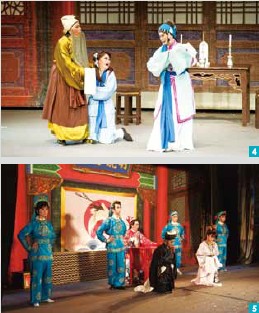

Taiwanese opera is the form of traditional art closest to the hearts and lives of the local people. In imperial days, when Taiwan was primarily a rural farming society, watching Taiwanese opera was a key form of leisure entertainment, and an important element in temple fairs giving thanks to the gods. As Taiwan entered the modern world, for a time the form was seen as lacking refinement, but today it’s regardedas a major cultural asset, is taken as a serious art form, and has even made an entrance onto the international stage. Many with a fondness for its aesthetics now enroll in classes to study its singing, makeup, and other elements, and even hitting the stage to perform it, for their own entertainment. Traditional Opera Nurtured and Cultivated in the Taiwan Soil Taiwanese opera is a local theatrical form that evolved from the humming song that the farming folk of the Lanyang Plain (蘭陽平原) used to sing during their leisure time over a century ago. Later, small song-anddance troupes became popular; their shows, called “chegu opera” (車鼓戲), featured ever more elaborate costumes, postures, and background musical accompaniment. This led to the emergence of more developed troupes and shows, which became popular at temple-front parades honoring the gods within. Eventually, the full-blown Taiwanese opera form emerged. Since all singing and speaking was in Taiwanese, and the melodies and plots were familiar to all Taiwanese people, the form became popular throughout the land. More and more professional companies were born. From its inception, Taiwanese opera was a key activity in local culture. Change and transformation has been constant over the form’s century-plus of existence, as the form absorbed elements from other types of theater genres popular in Taiwan, such as Beiguan opera (北管戲), Nanguan opera (南管戲), Beijing opera (京劇), Luantan opera (亂彈戲), and Gaojia opera (高甲戲). Each aspect has been transformed, from the musical instruments, make-up and costumes, props and scenery to the dramatic gestures, postures and operatic singing style, music scores, and performance contexts. Refinement has continued right down to the present day; what has never changed though is its intimacy, and popularity with the people, wherever it is performed: free shows on stages set up before temples,ticketed events in theaters, on television, in movies, and today on stage in modern theaters. Taiwanese opera is the dramatic genre, with the music and script, that best captures the beauty of the Taiwanese language and its emphasis on rhyme and antithesis. Populist Taiwanese opera has cultivated many fans and devotees. Famous local per formers such as Liao Chiungchih (廖瓊枝), Yang Lihua (楊麗花), and Sun Cuifeng (孫翠鳳) have huge fan followings. Liao Chiungchih, regarded as a national treasure, is chairperson of the Liao Chiung-Chih Taiwanese Opera Foundation for Culture and Education (廖瓊枝歌仔戲文 教基金會). Many in the audience are especially fond of the performances on outdoor stages, and when the specialized troupes that move about staging such shows release details on where a play will be performed, these fans will be sure to come and see the performance. Taiwanese opera shows performed at large-scale facilities feature especially beautiful scenery and dazzling lighting effects, the actors don particularly splendid costumes, and the famous four performing techniques— “singing, dialogue, acting, and acrobatics” (唱、念、作、打) – are even more elaborately designed. A “National Treasure” Taiwan Entertainer – Liao Chiungchih Liao Chiungchih, 77 years old this year, lost both her parents when she was a young girl, and was raised by her grandmother. She found herself alone after her grandmother became sick and passed away, and at 14 entered studies with the famous Taiwanese opera troupe Gold Mountain Music Society (金山樂社). She excelled at crying, and came to be called “Taiwan’s First Kudan” (臺灣第一苦旦), meaning its greatest master of female-role melodrama. Winner of many an arts and legacy award, she is constantly busy giving opera-skill workshops and speeches. She also teaches at the National Taiwan College of Performing Arts (國立臺灣戲曲學院), the only educational institution in Taiwan with a Taiwanese opera program. Studying Taiwanese opera has become popular all over Taiwan in recent years, and some universities have established Taiwanese opera clubs. Social education organizations and community colleges have opened classes. The Taipei Cultural Center (臺北市立社會教育館) and Dalongdong Bao’an Temple (大龍峒保安宮) have invited Liao to teach courses. Liao says that teaching opera to the general public is very different from teaching it to school students. There is an expression that goes “One minute on the stage, ten years of practice off the stage” (台上一分鐘,台下十年功), meaning that students must start by establishing a solid foundation, and must commit to years of study to complete their apprenticeship. But although the average class is just four months, an exhibition of what has been achieved during that time must be staged at the end, with students giving a performance. During each course there is only time enough to teach one play, so each student is assigned a role that they must specialize in, mastering the character’s lines, singing, postures and actions. A Primer on Taiwanese Opera Dadaocheng Theater 大稻埕戲苑 Dalongdong Baoan Temple 大龍峒保安宮 Zhongzheng Community College Datong Community College 大同社區大學 The main roles in Taiwanese opera are sheng (生), dan (旦), jing (淨), and chou (丑). Sheng denotes the male leads, the main types being laosheng (老生; older characters), xiaosheng (小生; younger characters), and wusheng (武生; martial characters). Dan refers to female leads, of which there are four types; xiaodan (小旦; younger females), laodan (老旦; older ladies), huadan (花旦; coquettes), and kudan (苦旦; sorrowful ladies). Jing are dignified, larger-than-life male historical figures of vivid personality such as Guan Gong (關公), Cao Cao (曹操), and Bao Gong (包公). Chou are comic figures. Each staged Taiwanese opera has its strengths and its own individual style, and the soul of each is the storyline. A well-constructed script brings the audience along on a roller-coaster ride of emotional highs and lows. Up on the stage, the male and female leads are the natural point of focus, and in addition to enjoying the visual aspect of the performance, audiences pay close attention to the singing and postures of the xiaosheng and xiaodan. The thrilling interplay of instrumental and percussion music is also a highlight, especially when the wusheng is on stage showing off his martial-arts prowess, which will often bring repeated cheers from viewers. According to a Chinese expression, “The layman watches the smoke and mirrors, the adept identifies the tricks of the trade” (外行看熱鬧,內行看門道). To become an adept yourself, take in a few wonderful shows, and develop your taste for the beauty of Taiwanese opera.

Information

Add: 8-9F, 21, Sec. 1, Dihua St., in Yongle Market

Tel: (02)2556-9101

Add: 61, Hami St. Tel: (02)2595-1676

Website: http://www.baoan.org.tw/ENGLISH/index.html

中正社區大學

Add: 6, Sec. 1, Jinan Rd. Tel: (02)2327-8441

Website: www.zzcc.tp.edu.tw (Chinese)

Add: 37-1, Chang’an W Rd. Tel: (02)2555-6008

Website: www.datong.org.tw (Chinese)

The makeup, costumes, poses and gestures, singing, lines, and props carried by each role are different. For example, the xiaosheng carries a folding fan, the xiaodan a round fan or floating fan, a handmaiden’s silk scarf or octagonal towel, etc. The xiaosheng and xiaodan are lead male and female roles, the former a handsome and refined character, the latter bright and delicate.

![Taiwan.gov.tw [ open a new window]](/images/egov.png)