One Set of Scissors, Infinite Designs--The Beauty of Paper-Cut Art

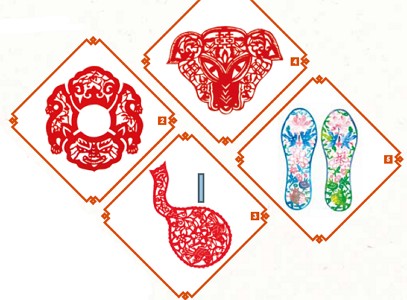

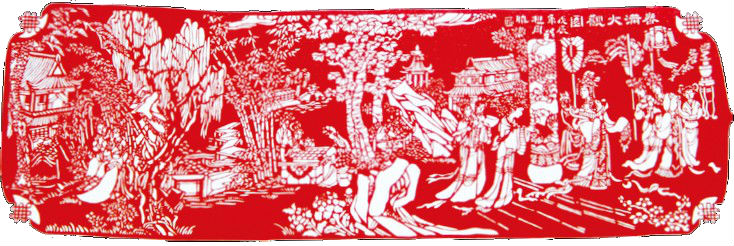

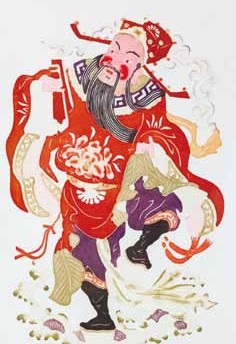

Designs Passed Down Through Countless Generations In the old days, because printing was not widespread and the multicolor gift-box packaging so familiar today did not exist, paper-cut art was also used for weddings and on other felicitous occasions. The xi (囍) or “double happiness” character, as well as auspicious peonies, would be cut and pasted on a xi he (囍盒) or “doublehappiness box.” Decorations pasted on a mirror were called jing hua (鏡花) or “mirror flowers.” Commoners would use paper-cuts called zhutou hua (豬頭花) or “pig head flowers/designs” and zhutui hua (豬腿花) or “pig leg flowers/designs” to represent the real thing. Elsewhere, paper-cut designs were borrowed from the traditional embroidery designs on shoes called xie hua (鞋花) or “shoe flowers/designs,” and on dudou (肚兜), a type of undergarment covering a woman’s chest and abdomen. Each of these paper-cut patterns, passed down generation after generation from long ago to the present day, has its own meaning. “National Treasure” Paper-Cut Master – Li Huanzhang An officially declared Taiwan “national treasure,” 90 year-old paper-cut master Li Huanzhang (李煥章) is a teacher who has long devoted himself to promotion of this land’s paper-cut cultural heritage. However, now in his tenth decade, his voice is strong and measured, and he is filled with energy. He teaches paper-cutting every Saturday morning at National Dr. Sun Yat-sen Memorial Hall, and some of his students have been with him for over a decade. When this class ends at noon, he throws on his backpack and heads out with a spry step to teach another class over at Xingtian Temple. When he was young he attended normal school in his hometown in China’s Shandong Province (山東省). War threw the country into chaos, however, and he left for Taiwan to live in exile. He’s lived in Taipei for 60 years, and taught at Zhongzheng Elementary School (中正國小) for thirty of them. During that time he came to know an official from the Department of Education (教育局), who noticed his talent at paper-cut art, asked him to teach classes, and arranged budgeting. Li was thrilled to share all he knew and to pass on and promote the art skills he had learned in his homeland, taking up the cause with alacrity and educating other teachers from inside and outside his school about paper-art culture. These teachers passed on their knowledge of the traditional art form to many students. In the past, paper-cutting was not considered a form of art. Instead, it was referred to merely as “using scissors to cut paper.” While gravers, a special type of cutting tool, have become universal in modern times, cutting has become carving, and designs have become more elaborate and varied. Among the designs that have become common are festival scenes, scenes from historical tales, nature scenes in the shanshui (山水) style, birds and flowers, fish and insects, Bei j ing-opera mas k s , historical figures – you name it. In the past Li has made papercut carvings of such Chinese classic stories as Dream of the Red Chamber (紅樓夢) , Water Margin (水滸 傳), and Romance of the Western Chamber (西廂記), and once spent three years on a 5-meter-long work entitled Lives of the Holy Immortals (87神仙傳). Though an icon in the world of paper-cut art, Li remains a dedicated student. Always open to change and transformation, he is currently studying Chinese ink-and-wash paintings as well as traditional Chinese paintings, introducing their color concepts to papercut art’s color-dye techniques. In the past, in his search for new inspiration and subject matter he spent more than a decade at the National Palace Museum and National Central Library, gathering pictures and calligraphy samples from copies of ancient books as reference for his paper-cut work. He has even collected materials on Western modern art, such as Matisse’s Fauvism work. Li has a collection of over 10,000 copies of designs in his home, clear evidence of his willingness and ability to incorporate new ideas. He also looks to non-conventional materials, utilizing traditional rice paper and cotton paper for his art along with silks and satins, which are more durable and long lasting. Li’s unquenchable thirst for the new and innovative is clear. Mastery – Achieved Only After Countless Failures Using specialist paper-cut scissors from Japan, Li deftly creates 3D “spring” (春) characters, cherry blossoms, pineapples, national flags, national emblems, and myriad other patterns. He recalls his days in his hometown, hearing the cry of peddlers coming into his alley calling out “Knife sharpening! Scissors sharpening!”Neighbors would come out all along the street to give their old knives and scissors to the master worker to grind and sharpen. In rural communities in early China, men tended the fields and women took care of such matters as making clothing, shoes, and headgear. During the Chinese New Year season households would come together in warm-spirited celebration, chatting about small matters and, often, creating paper-cut art – oxen in the Year of the Ox, horses in the Year of the Horse, auspicious characters such as fu (福; good fortune), shou (壽; longevity), and xi (喜; happiness). New art would be put up in wood-frame windows to replace the fading works from the year before, greeting the arriving year and seeking to attract luck and fortune as well. A layer of Tung oil would be spread on the paper-cuts used as window decorations to prevent them being ruined by the snow and cold wind and rains coming down from the north. With the passing of the years, a true paper-cut culture came into being.

In rural communities in early China, men tended the fields and women took care of such matters as making clothing, shoes, and headgear. During the Chinese New Year season households would come together in warm-spirited celebration, chatting about small matters and, often, creating paper-cut art – oxen in the Year of the Ox, horses in the Year of the Horse, auspicious characters such as fu (福; good fortune), shou (壽; longevity), and xi (喜; happiness). New art would be put up in wood-frame windows to replace the fading works from the year before, greeting the arriving year and seeking to attract luck and fortune as well. A layer of Tung oil would be spread on the paper-cuts used as window decorations to prevent them being ruined by the snow and cold wind and rains coming down from the north. With the passing of the years, a true paper-cut culture came into being.

From Cutting Paper to Carving – From Paper to Silks and Satins

From Cutting Paper to Carving – From Paper to Silks and Satins

When students ask him how he has attained such a high level of skill, Li always replies: “Everyone always concentrates on the successes. They don’t look at the constant, relentless practice I’ve put in at home, and the countless failed works.” He sees paper-cutting as an art with its own culture, in which one cultivates one’s temperament to be able to enter a state of pure calm that allows intense thought concentration. There are low barriers to entry, and costs are low, but the gifts you present to family and friends earn you goodwill and high respect. These things provide strong encouragement for more people to try their hand at the form. Since Chinese New Year is arriving soon, we asked Master Li to demonstrate how to craft the character for “spring”, a common, auspicious seasonal decoration, so friends from overseas can experience the beauty of the papercut experience for themselves.

When students ask him how he has attained such a high level of skill, Li always replies: “Everyone always concentrates on the successes. They don’t look at the constant, relentless practice I’ve put in at home, and the countless failed works.” He sees paper-cutting as an art with its own culture, in which one cultivates one’s temperament to be able to enter a state of pure calm that allows intense thought concentration. There are low barriers to entry, and costs are low, but the gifts you present to family and friends earn you goodwill and high respect. These things provide strong encouragement for more people to try their hand at the form. Since Chinese New Year is arriving soon, we asked Master Li to demonstrate how to craft the character for “spring”, a common, auspicious seasonal decoration, so friends from overseas can experience the beauty of the papercut experience for themselves.

Information Li Huanzhang Paper-Cutting Courses (Advance registration required; fee charged) Xinyi Community College Taipei City 臺北市信義社區大學

Time: Thurs 19:00~21:30

Tel: (02)8789-7316, ext. 102 (telephone registration)

Website: www.xycc.org.tw (Chinese) National Dr. Sun Yat-sen Memorial Hall 國父紀念館

Time: Sat 10:00~12:00

Tel: (02)2758-8008, ext. 715, 716

Website: www.yatsen.gov.tw (Chinese) Hsing Tian Kong Library 財團法人台北行天宮附設玄空圖書館

Time: 13:40~15:40

Tel: (02)2713-6165, ext. 355

Website: www.lib.ht.org.tw/eng/index.html (Chinese)

![Taiwan.gov.tw [ open a new window]](/images/egov.png)