The Art of Seal Carving--Beauty in a Small Square

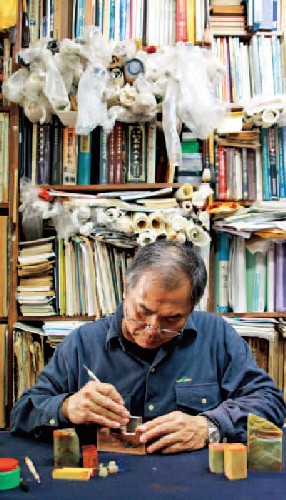

Worlds of Beauty in Small Squares – Seal Carving Appreciation Chen Hongmian has been studying the art of seal carving for 38 years. Winner of a Sun Yat-sen Art and Literary Award for Creativity in Seal Carving, the top“Seal Cutting Academic Society Award for Young Artists”, and many other honors, his fame as an artist is widespread. Chen is founder of the Taiwan Seal Association and also author of a number of publications that promote the art of carving seals. To appreciate seal cutting as art, he says, there's no need to dwell on the meaning or interpretation of the text itself; rather, the aesthetics dwell within the line formation, arrangement, and unity of the whole that you find within the character cases. This allows a more natural intuition of the artistic conception – the message and mood the carver has sought to convey. Thus approach a work of Seal designs are not always limited to purely character s , however. For example, the Huaya or“Flower Signature”Seal, which became popular in the Yuan Dynasty, features the family name at the top and a flower or other artistic mark at the bottom, creating a unique identifier. Both the marks and the impressions come in many shapes – long, rounded, gourd-shaped, animal-shaped, and even more imaginative designs. Seals also feature auspicious animal symbols carved along the edges, among them the dragon, phoenix, turtle, and lin (a mythical animal resembling a deer). A device often used to Seal-Carving DIY The basic tools needed (knife, seal stone, seal bed, and seal-character dictionary) are all available at numerous Taipei shops, including Hui Feng Tang, You Sheng Chang, Mei Yu Tan, and Jia Yi Meishushe. According to Chen,“Do not over-prepare; a basic flat knife will do. Select a pyrophyllite (also known as pencil stone) with a hardness of 2~2.5 degrees, a dedicated seal stone that is firm and solid, and a proper seal-engraving character dictionary. Adjust the character-size ratio, rub impressions of the characters on the seal surface, pick up the knife, and you are ready to begin sculpting your lines.” “Studying seal carving is not difficult,”says Chen,“but you must concentrate on perfecting each step before proceeding, and the only way to improve is through experience, with a teacher for guidance.”He also warns that once you seek to unearth this art's secrets, and they begin to reveal themselves to you, you'll fall in love and be hooked forever. Where to Study Seal Carving in Taipei Chiang Kai-shek Memorial Hall Where to Buy Seal Carving Materials in Taipei Hui Feng Tang Related Exhibitions Sharing Treasures: A Special Exhibition of The World of Engravings and Poems  Seals (also known as chops) are carefully carved stone stamps used by the Chinese instead of a signature. Apart from being a convenient way to prove one's identity, however, each seal, however small, is

Seals (also known as chops) are carefully carved stone stamps used by the Chinese instead of a signature. Apart from being a convenient way to prove one's identity, however, each seal, however small, is

also a representation of a person's deeper self-identity and status. Seal carving is a classic Chinese art form that can be traced back 3,700 years to the Shang Dynasty, its origins lying in the carving of

dies used to create impressions on pottery, recording such information as the owner's family/clan emblem, name, official position, organization, or shop name. In more recent times other details such as birth date and age may be also be carved. Seals have also been created simply for personal collections, for use as marks by painting and calligraphy aficionados, and as permanent records of favorite maxims, aphorisms, and poetry. The range of fonts and lines seems to know no bounds, and the demands on the seal-maker in terms of time and skill great, placing the“craft”of sealcutting firmly in the realm of fine art. During the Han Dynasty, seals came to be used to create protective marks on letters and large items being sent to others. In those days writing was done on bamboo or wood slips, and after they were

During the Han Dynasty, seals came to be used to create protective marks on letters and large items being sent to others. In those days writing was done on bamboo or wood slips, and after they were

fastened together with string, paste would be applied over the knot and an identification impression made with a seal. Because the area of the paste was limited and a seal had to be carried on one's person, it was small – just 1 or 2 centimeters wide, with a hole drilled through to allow it to be carried on a string or cord. When paper was invented, seals found a much wider range of uses, both seal and character size were expanded, and greater variations in font and structure emerged. During the Song and Yuan dynasties the literati developed a fascination with seal carving, and the aesthetics of the composition and script used were raised to a higher plane, elevating seal cutting to the status of an art form.

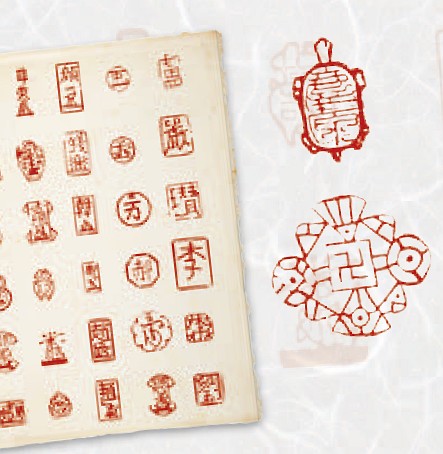

calligraphy as any other work of art. The main forms used for seal characters, says Chen, are the Oracle Bone Script, Bronze Script (used on bells and ceremonial cauldrons), Large Seal Script, and Small Seal Script. Some, though not many, use the Regular Script, Cursive Script, Semi-Cursive Script, and Clerical Script. Carving techniques are the Zhu Wen or Red Character style, meaning the seal is carved in relief, with imprints of character lines in red ink, and the Bai Wen or White Character style, with the characters incised and imprinted lines in white, with a red background. In terms of the classic yin/yang negative/positive dichotomy, the first style is yang carving, the second yin carving. The arrangement, the density and spacing, the lightness or heaviness of the structure, and the judicious leaving of blank areas heighten the effect of the impression.

The main forms used for seal characters, says Chen, are the Oracle Bone Script, Bronze Script (used on bells and ceremonial cauldrons), Large Seal Script, and Small Seal Script. Some, though not many, use the Regular Script, Cursive Script, Semi-Cursive Script, and Clerical Script. Carving techniques are the Zhu Wen or Red Character style, meaning the seal is carved in relief, with imprints of character lines in red ink, and the Bai Wen or White Character style, with the characters incised and imprinted lines in white, with a red background. In terms of the classic yin/yang negative/positive dichotomy, the first style is yang carving, the second yin carving. The arrangement, the density and spacing, the lightness or heaviness of the structure, and the judicious leaving of blank areas heighten the effect of the impression. Sometimes, to accommodate the allocation of character strokes, the stroke will be curved or elongated to attain harmony. A famous example of this is Wu Changshuo's“Yuan Ding Mo Xi”,

Sometimes, to accommodate the allocation of character strokes, the stroke will be curved or elongated to attain harmony. A famous example of this is Wu Changshuo's“Yuan Ding Mo Xi”,

carved on a piece of the renowned Shoushan stone, currently in mainland China's Zhejiang Provincial Museum. The character ding has only two strokes, and in a bold move to attain balance with the other three characters Wu used a huge dot to represent the character.“When appreciating such works,”says Chen,“see how the composition is rendered upright and foursquare, the cutting firm and confident, and inspect whether the juxtaposition of red and white displays a refined aesthetic sensibility.”

heighten an impression's aesthetic appeal is to carve a horizontal or vertical line in the middle – or both, forming a cross – to form character domains. In the Han Dynasty a popular device (called the Bird and Worm Seal) used on private seals was to carve a bird head) at the beginning of a character or at the end, making the characters flow as though formed into a long dragon. In some cases fish shapes were substituted, the fish being another auspicious animal, symbolizing wealth and social position. To get a better idea of this beautiful art form, pay a visit to the National Palace Museum to take in the permanent exhibition Sharing Treasures: A Special Exhibition of Antiquities Donated to the Museum, which features a superb selection of exquisite seals owned by famed historical figures, the seals serving as priceless witnesses to both their owners' and to China's history. Admire as well the different types

To get a better idea of this beautiful art form, pay a visit to the National Palace Museum to take in the permanent exhibition Sharing Treasures: A Special Exhibition of Antiquities Donated to the Museum, which features a superb selection of exquisite seals owned by famed historical figures, the seals serving as priceless witnesses to both their owners' and to China's history. Admire as well the different types

of beautiful stones used and the sensual aesthetics of both the characters and the many scripts used to write them. Another fine idea is a trip to the Museum of Medical Humanities and the exhibition The World of Engravings and Poems, showing until March 31st, which revels in the art of the seal married with that of the classical poetry. Most seal-carving experts are also highly skilled at calligraphy, masters of the various styles described above (such as regular and clerical script), and are also masters at both carving with and sharpening the seal-carver's most important tool, the knife. Another indispensable asset is development of a heightened sense of aesthetics. Chen teaches the art at Chiang Kai-shek Memorial Hall and National

Most seal-carving experts are also highly skilled at calligraphy, masters of the various styles described above (such as regular and clerical script), and are also masters at both carving with and sharpening the seal-carver's most important tool, the knife. Another indispensable asset is development of a heightened sense of aesthetics. Chen teaches the art at Chiang Kai-shek Memorial Hall and National

Taiwan Arts Education Center, and has taught many students who have not had a base in calligraphy, but who have nevertheless been able to carve beautiful works. Says the master:“With just a basic sense of beauty and a nimble hand, you too can create seal-carving art.”

Information

Add: 21, Zhongshan S. Rd.

Tel: (02) 2343-1100, ext. 1125

Website: www.cksmh.gov.tw

National Taiwan Arts Education Center

Add: 47, Nanhai Rd.

Tel: (02) 2311-0574, ext. 117

Website: www.arte.gov.tw

Add: 123, Sec. 1, Heping E. Rd.

Tel: (02) 2321-1380

You Sheng Chang

Add: 23, Sec. 1, Heping E. Rd.

Tel: (02) 2341-7580

Mei Yu Tang

Add: 142, Shida Rd.

Tel: (02) 2369-2177

Jia Yi Meishushe

Add: 83-1, Sec. 1, Heping E. Rd.

Tel: (02) 2351-7733

Antiquities Donated to the Museum

Venue: Gallery 303, National Palace Museum

Add: 221, Sec. 2, Zhishan Rd.

Tel: (02) 2821-2021

Hours: Open year-round, 08:30~18:30; hours extended

to 20:30 Sat, free entry during extension

Website: www.npm.gov.tw (Chinese)

Venue: Museum of Medical Humanities

Add: 1, Sec. 1, Ren'ai Rd.

Tel: (02) 2312-3456, ext. 88929

Hours: Until 3/31, Tues~Sun 09:30~16:30 (closed Mon and national holidays)

Website: mmh.mc.ntu.edu.tw (Chinese)

![Taiwan.gov.tw [ open a new window]](/images/egov.png)