Calligraphy Brushes From a Bygone Era Make a Comeback in Taiwan

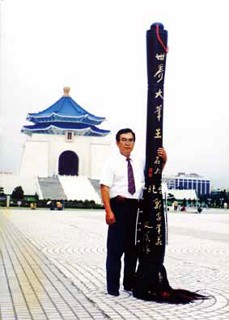

The Evolution of Chinese Calligraphy and Brush-Making Ink was first made in China as early as the 23rd century BC. These inks were composed of natural dyes from plants, animals, and minerals. The most common type of ink in early times was made of graphite in an aqueous solution, which was applied to the raised surface of pictures or characters carved into stone. By the 12th century BC, a type of ink made of pine soot, lamp oil, animal glue, and musk was in common use. Around the time of the Warring States Period (戰國 時代), the first solid inks, precursors to modern ink sticks, first appeared. These small ink pellets could be ground on ink stones and mixed with water when needed. Improvements in ink and papermaking technology also generated the need for a refined device for applying the ink, and so the ink brush was invented. The oldest intact brush we have today comes from around the same time that ink pellets started being used. It was made of a wooden stalk and bamboo tube that secured the bundle of animal hair to the stalk. Bamboo later became the norm for the brush stalks, though a wide variety of other materials could be used, such as jade, gold, silver, ivory, and different types of wood. The most common hairs used for the tip were goat, rabbit, wolf, and weasel, though more exotic hairs such as tiger and fowl were occasionally used. The Guo Family Ink Brush Shop Guo Wenxi first learned how to make brushes in the traditional manner in Tainan when he was 13. Following the early death of his father, Guo’s eldest brother picked up the art form under the tutelage of a master from Fujian Province (福建省) and taught it to his brothers and male cousins. “Making ink brushes is so difficult that I had to watch for six months before I was allowed to try. We used to work 12-hour-plus days in the shop, trying to keep up with demand.” Following his military service, Guo moved to Kaohsiung (高雄) to set up shop. Around the same time, education reforms were made in Taiwan so that students were no longer required to use ink brushes. As a result, Guo’s business went into sharp decline, and things only got worse as modern plastic pens gained in popularity across Taiwan. That’s when he decided to move to Taipei and opened the Guo Family Ink Brush Shop (郭家筆墨莊) near the former Taipei City Hall in Zhongzheng District where many government offices, in which traditional writing implements were still required for official documents, were located. “Back in those days we sold exclusively to government officials and calligraphy enthusiasts. The former were our best customers, with their huge government budgets. They would just strut in, point at this and that, and spend thousands of dollars in less than a minute.” Still, business was not what it used to be. All that would change when the baby hair brush fad erupted in Taiwan in the 1980s. Adapting to a Niche Market: Baby Hair Brushes According to Guo, ink brush production came to a halt in China during World War II and the ensuing civil war. As a result, Taiwan turned to Japan for supplies. It was when Guo’s older brother was making purchasing expeditions in Japan that he first noticed baby hair brushes were still popular there, and he thought of pushing the idea in Taiwan. For whatever reason, the baby brush phenomenon did take off on its own in Taiwan, and the Guo’s relate that the baby brush craze in fact saved their business. “My son had just finished doing his military service and didn’t really want to take over the family business. But upon my insistence, and his realization of the potential profitability in the baby hair brush industry, he decided to accept the challenge.” Guo claims that his shops are unique in that they still make every part of the brush by hand, a process that involves no less than 80 steps. Many other shops simply purchase parts and assemble them. The Chinese believe that a lock of baby hair is one of the three “treasures” associated with the birth of a child, the other two being the baby’s umbilical cord and footprint. The Guo Family Ink Brush Shop provides custom-made boxes that include all three. The interior of the box’s lid bears the child’s footprint, while the baby hair brush and a name stamp containing the baby’s umbilical cord are contained within. The baby’s name and words of good luck are carved into the exterior of the box, providing a memento to be cherished for a lifetime. Besides making baby hair brushes, Guo has also made a number of oversized ink brushes, putting him in the media spotlight. His largest usable ink brush measured a staggering 338 centimeters and was featured in an exhibition at the National Chiang Kai-shek Memorial Hall (國立中正紀念堂), where it was used to paint enormous characters on the ground. But Guo’s all-time largest brush is over four meters long, weighing in at 130 kilograms, making it the world’s largest ink brush, but only a superhero would possess the strength to lift this titanic writing implement. Choosing a Quality Ink Brush  In China and throughout the East Asian cultural sphere, calligraphy is a highly revered form of art. The graceful strokes of masterful calligraphers exude an elegance that harks back to an era when writing was exclusively a pastime of the literati. The Four Treasures of the Study (文房四寶), namely the brush, ink, paper, and ink stone were all invented in China. While usage of ink brushes has declined with the takeover of modern pens, they are making a comeback in Taiwan in the form of human baby hair brushes. We recently met up with veteran ink brush-maker Guo Wenxi (郭文溪) to find out how the ink brush business is doing these days.

In China and throughout the East Asian cultural sphere, calligraphy is a highly revered form of art. The graceful strokes of masterful calligraphers exude an elegance that harks back to an era when writing was exclusively a pastime of the literati. The Four Treasures of the Study (文房四寶), namely the brush, ink, paper, and ink stone were all invented in China. While usage of ink brushes has declined with the takeover of modern pens, they are making a comeback in Taiwan in the form of human baby hair brushes. We recently met up with veteran ink brush-maker Guo Wenxi (郭文溪) to find out how the ink brush business is doing these days. As Chinese writing developed and sets of characters became standardized, calligraphy became increasingly stylized. A multitude of factors can affect the quality of a calligrapher’s work, from the characteristics of the brush, ink and paper to the skills and techniques used, including the inclination, direction and pressure applied to the brush. The calligrapher’s body position and manner of holding the brush dictate the fluidity of the strokes, and so masters of calligraphy consider movement a key aspect of their art form.

As Chinese writing developed and sets of characters became standardized, calligraphy became increasingly stylized. A multitude of factors can affect the quality of a calligrapher’s work, from the characteristics of the brush, ink and paper to the skills and techniques used, including the inclination, direction and pressure applied to the brush. The calligrapher’s body position and manner of holding the brush dictate the fluidity of the strokes, and so masters of calligraphy consider movement a key aspect of their art form. Calligraphy developed in parallel with ink and wash paintings, and both were considered educational pursuits requiring years of training. Practice typically involved the meticulous copying of exemplary works. Calligraphy was a component of the imperial examinations for government positions. In Taiwan students were still required to write their test compositions using ink brushes until the 1960s.

Calligraphy developed in parallel with ink and wash paintings, and both were considered educational pursuits requiring years of training. Practice typically involved the meticulous copying of exemplary works. Calligraphy was a component of the imperial examinations for government positions. In Taiwan students were still required to write their test compositions using ink brushes until the 1960s. Legend has it that in the Tang Dynasty (唐朝) there lived a young man whose family was too poor to buy an ink brush before he went to the capital to take the civil service examination. The innovative mother used a lock of her son’s own baby hair, which she had saved since his birth, to make a brush for him. When the man aced his tests, the baby hair brush, later also referred to as “champion brush,” (狀元筆) was hailed as a symbol of good luck. The tradition also spread to Japan, where it has persisted into modern times.

Legend has it that in the Tang Dynasty (唐朝) there lived a young man whose family was too poor to buy an ink brush before he went to the capital to take the civil service examination. The innovative mother used a lock of her son’s own baby hair, which she had saved since his birth, to make a brush for him. When the man aced his tests, the baby hair brush, later also referred to as “champion brush,” (狀元筆) was hailed as a symbol of good luck. The tradition also spread to Japan, where it has persisted into modern times. Currently the bulk of the Guo family’s production is concerned with making baby hair brushes, and business is thriving. At the age of 72, Guo himself still makes the brushes, along with his son’s wives, while his second oldest son focuses on marketing and picking up the locks of hair from clients in Taipei. Another shop is run in Hsinchu (新竹) by Guo’s eldest son, whose wife is currently teaching Guo’s 28-year-old grandson the art form late at night when he gets home from his day job. More of Guo’s relatives run shops of the same name in Kaohsiung, Tainan (臺南), and Chiayi (嘉義).

Currently the bulk of the Guo family’s production is concerned with making baby hair brushes, and business is thriving. At the age of 72, Guo himself still makes the brushes, along with his son’s wives, while his second oldest son focuses on marketing and picking up the locks of hair from clients in Taipei. Another shop is run in Hsinchu (新竹) by Guo’s eldest son, whose wife is currently teaching Guo’s 28-year-old grandson the art form late at night when he gets home from his day job. More of Guo’s relatives run shops of the same name in Kaohsiung, Tainan (臺南), and Chiayi (嘉義). According to Guo, there are a few important things to check for when selecting the perfect brush, which depend largely on what you want to use the brush for. If you intend to use it for calligraphy, opt for a mixed-hair brush, which typically contains goat, pig, and/or rabbit hair. Check closely to make sure that the brush hairs are not curved and look neat. If you will be using the brush to paint, you want to get one made of weasel hair for painting bamboo, goat hair for flowers, and pig hair for mountains or other landscapes. Generally speaking, harder brushes are easier to work with. After purchasing a brush, you don’t need to wash it. Just press it down gently on paper before using to loosen it up. Rinse with water after using, pointing the hairs in the same direction as the flow of water, and then squeeze the water out of the brush by hand. Before using the brush the second time and henceforth, lay the brush horizontally with the hairs submerged in a saucer of water, allowing them to soak for five minutes.

According to Guo, there are a few important things to check for when selecting the perfect brush, which depend largely on what you want to use the brush for. If you intend to use it for calligraphy, opt for a mixed-hair brush, which typically contains goat, pig, and/or rabbit hair. Check closely to make sure that the brush hairs are not curved and look neat. If you will be using the brush to paint, you want to get one made of weasel hair for painting bamboo, goat hair for flowers, and pig hair for mountains or other landscapes. Generally speaking, harder brushes are easier to work with. After purchasing a brush, you don’t need to wash it. Just press it down gently on paper before using to loosen it up. Rinse with water after using, pointing the hairs in the same direction as the flow of water, and then squeeze the water out of the brush by hand. Before using the brush the second time and henceforth, lay the brush horizontally with the hairs submerged in a saucer of water, allowing them to soak for five minutes.

![Taiwan.gov.tw [ open a new window]](/images/egov.png)